The insightful Peter Gerdes has a new post about Art appreciation that is absolutely worth a read.

His case that appreciating art and the thrill of video games are “hijackings” of the evolutionary circuitry is one I basically agree with and will assume throughout this post. As he puts it, “Just as with video games, we need to be careful not to let the feeling that we are making progress, discovering new insights etc.. etc.. convince us we are doing something more than playing a game.” That’s true, but I also think that not all games are created equal. To that end, the “easy mode” of this post is to skip to the tl;dr. But if you want to meander a little metaphorically, let’s talk about the Quality of games, both video and status.

As I put it to Peter in our discussion in the comments,

“I think Monopoly is "objectively" a terrible game. It is poorly designed, long, and not particularly interesting in the gameplay dynamics. Settlers of Catan, while structurally quite similar, is simply "better" in ways that align with my intuition and ideals of game design. And I think that when people who enjoy Monopoly play Settlers instead, they have more fun (obviously this isn't universal, but it's also not far from it ime). Making Settlers the "default" board game over Monopoly is a sign of culture moving in a positive direction, and is part of making the world more fun.”

Just as all games are not equally valuable, so too are there massive differences in the quality of Art. I want to sketch out a few of my intuitions on the topic, relying on Gerdes’ video game metaphor to keep things manageable.

Aesthetic judgement, hereafter I’ll just call it taste, comes from a (mostly inchoate and implied) model of what Good Art is, and that determines how you react to cultural input. This model is different than the actual emotions induced by your experience with particular pieces of art, which are points of data in your mental landscape, a multidimensional territory primarily defined by your memories of the experience. Your judgement of a work of Art is basically the specific map of the mental journey the Art puts you through, compressed to be legible to whomever you’re trying to communicate with (including your future self). Thus, saying something was “good” or “bad’ doesn’t say much, unless you have an idea of a person’s standards and previous aesthetic judgements. But if someone says, “good, because of A, B, and C”, or “mixed, because of X, Y, and Z”, they’re actually providing a ton of other information about their taste and previous aesthetic experience. This is important, because one of the things Art does is communicate emotional understanding, and a great deal of meaning comes from having shared cultural and emotional cognizance of the world.

If you understand someone’s taste and know what they’ve seen, you can predict what new things they’ll enjoy. If you’re right about that prediction, you have just made your friend’s day and improved your bond. If you’re wrong and they don’t like it, you have the opportunity to improve your model of your friend, or your model of Art in general. Either way, the act of recommending, discussing, and experiencing Art all goes together as one of the most human acts around, at least based on how much time we spend on it. Making recommendations the sole purview of Netflix algorithms and marketing executives is Bad, actually. I don’t think we can make the world better simply by consuming Better Content, but I suspect we can only make the world worse by consuming Bad Content.

Having “good taste” could be summarized as having the right frames to communicate about Art with other people or groups. If you have it, then people start viewing Art through your frame, and your model of Art gets transmitted and more persuasive due to network effects. Moreover, if you’re a creative yourself (and I’d argue we shouldn’t limit that term to those who create things professionally - we’re all Creatives!), having good taste gives you examples both to aspire to and to denigrate/improve upon. Interrogating our aesthetic choices and emotions is what allows us to improve our internal models of Artistry, and those improved models enable better communication about what Art means, so that we can find the works and people that resonate.

Just as there are fitness landscapes which describe how organisms evolve over time, I think there are "aesthetic fitness" landscapes which determine what is considered Art. The "peaks" of those aesthetic landscapes will obviously vary over time, and what is considered "great" will often not be remembered later, and there's probably no way to say which things are "objectively" Good. But, I'd argue if you cultivate taste, you can discern Better from Worse.

I agree with Gerdes that dense, often impenetrable texts like Heidegger are not a particularly good use of time, despite what many of their acolytes say. But that’s an argument about marginal utility, not an argument about the inherent Value of a work. To analogize back to videogames, I’d say it’s akin to the argument (some of my friends make) that playing something like Elden Ring and looking up info about what to do on the internet (walkthroughs, etc.) is “cheating” on par with an invincibility hack. Such an artificial limitation probably does make you better by the end of the game, simply because when you have to work everything out yourself, you spend more time on it, and I’ll bet reading Heidegger provides hard-won insights that feel good because they are hard-won.1 If philosophical or aesthetic insight is all ultimately a game, and you enjoy playing it, why should it matter whether you do it “efficiently” or not? What’s the harm of playing on hard-mode?

Obviously I can only speak for myself, but one of my aesthetic values is recognizing the breadth of creative work that takes place in the world. There is so much Art in the world, and I’ll never experience more than a fraction of it. Therefore, I’d like to spend my time getting a broad lay of the aesthetic landscape, and go more deeply into the “best” works of different mediums/genres, since I predict that will offer the most “bang for your buck” in terms of increasing my discernment. That discernment - increasing the fidelity of my mental model of Art in ways that make me better able to discuss it and recognize interesting features of it and/or my emotional relationship to it - is what allows me to share in others’ interpretations of Art and try to confer my own to them. Thus, it’s an investment, in this case in the shared endeavor of human creativity, which is what makes all the economic metaphors we’ve been using make sense for creative work which (at least in theory) occurs without economic motivations.

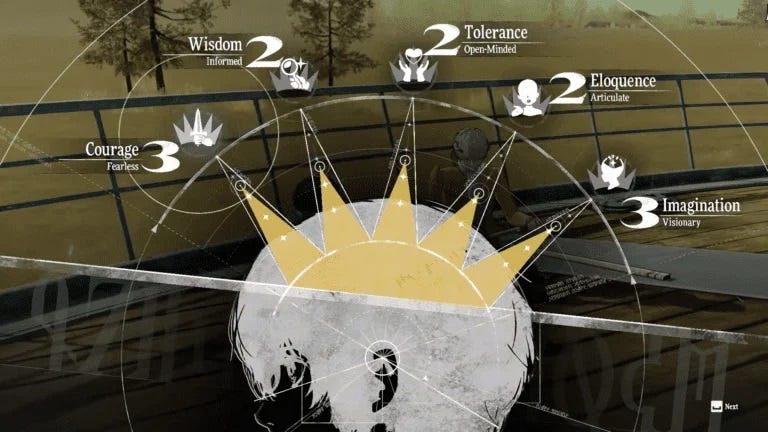

What, exactly, am I investing in by writing this? Well, in the video game Metaphor: ReFantazio, the protagonist has a list of Royal Virtues, which represent his experience and abilities in different areas.2

Certain parts of the game are inaccessible until you’ve “leveled up” these virtues a certain amount, and I suspect Art works in a similar fashion - you don’t know what you’re missing until you’ve unlocked the ability to understand it. Of course, there aren’t just 5 virtues available to Artists, each medium may use different ones, and those virtues may or may not overlap. But, that still leaves a multivariate representation of “skill” a person may require to make a work “accessible,” and there’s completely different sets of skills to produce your own Art or to make your perspective understood by others.

I think reading Heidegger thoroughly or playing Dark Souls to mastery is the equivalent of going from 9 to 10 in one of these skills. It’s potentially valuable and interesting, but likely there’s a “better” use of your time when there are whole virtues you simply haven’t tried to cultivate (or genres of Art you simply don't engage with). I think the investment of this essay is worth it, simply to have a tangible record of my thoughts that I can point to when I say I have deeply considered something, and want to make a recommendation.3

Of course, there are plenty of other, more valuable reasons to develop your taste more intentionally.

“The reason you'd want to be able to do that is to spot Talent and aesthetic judgement in others and encourage them to develop it. That way, you can identify people with potential to be future Steven Spielbergs or Pablo Picassos and encourage them to pursue it. Spielberg doesn't make movies no one else could make, but his cinematic intuition is so strong that the average quality of his movies is so high that he can set a higher standard for directors to live up to, and those standards make the culture better. Picasso, even if you don't particularly like his stuff, was genuinely new in a way that pushes the aesthetic frontier out, allowing future artists to work in new ways. Both kinds of "genius" should be supported, but I don't think that happens unless you have large swaths of society thinking and arguing about their aesthetic opinions, and giving status to those people who seem to be doing things differently than everybody else”.

Of course, this whole essay, just like anyone talking about aesthetics “in general”, is self-serving. I want people to show more breadth and depth in the kinds of Art they discuss, because that’s where my particular aesthetic model has the best chance to shine. I love the “ahh hah” moments when you notice references to other works and ideas in something, and explaining why those references were skillful/unskillful when discussing the work with others. If that kind of thing gains more cultural cachet, then I will be considered to have better taste. I am anti-mediocrity (including premium mediocre), enjoy creative reinterpretations of great works, and insane theories that turn leaden prose into gold. I want to see more of that kind of thing in the world, and this blog is a vehicle for me to encourage that. Instead of relying on Algorithms to shape our media diet (even really powerful ones), I think the world would be served by individuals developing more discerning tastes. We need more contrarians if we’re going to recognize great Content, and more people who are willing to push the aesthetic frontier boundaries if we want to find fertile soil for future artistic fruits.

TL;DR

In the time I had “finished” this essay, but before I had edited and published it, the inimitable @Defender had a thread which effortlessly conveys much of what I was trying to say:

If I was worried about prestige, getting outshone by a twitter thread would be bad for me. But since I’ve already confirmed I am somewhat lacking in good taste, it instead emboldens me to know others are thinking along similar lines. Plus, it’s just good irony to have a more succinct version of your thoughts appear before you can finish them. So, much like reading Being and Time, I can’t recommend the rest of the essay as an efficient use of your time. But, if you want an exploration of literary theory and aesthetics driven primarily by metaphors from video games, that’s clearly a game I enjoy playing despite the low payoff. I suppose that makes this entire post an exercise in Theory Grinding.

I haven’t read Heidegger myself, though I did read some of the original works of Kant and Fichte, before ultimately deciding that summaries written by others were a better use of my time (a choice it sounds like Peter would approve of).

These Woke kids and their virtue signaling in video games. Gamergate is clearly still being fought ;)

I discovered recently this is important to me because lately I’ve been giving my friends very tailored media recommendations, and they consistently come back with accolades on my good taste since they enjoyed them so much. But how can I recommend something to relative strangers on the internet? Well, if you have slogged through the rest of this essay and read the footnotes, I know you won’t be intimidated by something unusual, so it’s here I can recommend the video game 13 Sentinels: Aegis Rim, and the show Scavengers’ Reign. I consider them both the recent pinnacle of sci-fi storytelling in their respective mediums, so I doubt you’ll be disappointed (and if you are, I owe you an apology in the comments).